CHAPTER 4

Team leadership (management) is one of the fundamental roles of an entrepreneur. On the other hand, the ability to lead (occasionally or permanently) others is a desirable quality for every individual. Any responsible citizen does not wait to be led, but allows themselves to be led when necessary (by someone better suited), and also takes the initiative to lead others if they are more competent in that particular situation (and accepted!). Furthermore, good self-leadership in one’s own life is a basic duty of every individual. That is why civic education includes basic concepts regarding the art of leadership.

Every team-building instructor is a sort of manager, and every manager (director, boss) can become (and it would be beneficial to become!) a sort of team-building instructor for the team they lead. In fact, they should be the first to foster and create team spirit, to encourage subordinates (or rather – colleagues) to surpass themselves (and thereby increase personal and collective productivity). The manager (entrepreneur) can achieve this both through team-building exercises (taken from this course or inspired by it and adapted to the respective conditions) and through other means of action learned in entrepreneurship courses – or civic education courses. Of course, there is also the possibility for the manager to hire a specialized instructor for this purpose.

However, the issue is not whether the manager personally handles team-building or hires an external specialist, but whether they accept and embrace the idea of teamwork – as its implementation means (for many vain bosses) a decrease in their privileged status.

4.1. The Role of the Instructor

Collaborative games are not just play; they are a very powerful educational tool. The role of the instructor is even greater when the purpose of the games is not only to educate character (a social requirement) but also to change the social attitude of the participants (a patriotic requirement).

The Teambuilding instructor is a very important figure from a social perspective. Through their activities, they shape healthier and livelier individuals who think better for the collective interest, better and more efficient citizens.

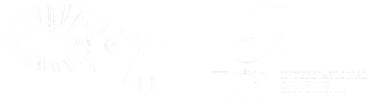

The tasks of the instructor are:

- to lead the group’s activities;

- to plan the activity; the games must meet the group’s needs, and the rules of the games will be adapted to the group’s specific nature and situation.

- to prepare the group for the session, activity;

- to explain the rules of the game;

- to supervise the conduct of the activity;

- to maintain discipline and prevent accidents;

- to enthuse and motivate group members;

- to understand the experience gained from the game by discussing it after the game ends;

- to be enthusiastic. Enthusiasm is contagious;

- to increase their professional competence.

The Teambuilding instructor cannot be just a simple sports teacher, or a form tutor, or a tour guide, or a naive enthusiast, or a bureaucrat, etc. They must have a mission, an intention, a purpose, a belief.

To achieve a comprehensive and favorable influence of organized play, the instructor’s permanent and creative participation is necessary. If they allow students to play and start reading the newspaper, or engage in conversation with an attractive spectator, the effect of the players’ activity decreases visibly.

On the other hand, when the instructor only sees and conveys to the participants the physical effort part of the game, or the pursuit of measured performance, or the “win,” they lose, and alongside them, all those guided lose many collateral values, some of which may be much more important:

- overcoming personal psychological barriers (“this cannot be done!”, “I’m afraid to jump,” etc.),

- the need for collaboration (“I don’t know these people, how will I get them to work together?”),

- the need for organization and assigning tasks within the group (“why should I listen to this person, is he smarter than me?”),

- understanding the need to help and support teammates (“if he’s foolish and jumps in, he’ll fall anyway”),

- realizing that girls can also perform “boy” tasks, and so on.

The fact that they are a leader and lead the group should not serve to boost the instructor’s ego, but to develop the physical and spiritual abilities of the players. Often, the group copies the boss’s moods. So the instructor is not allowed to be sad, pensive, sick, pessimistic, fault-finding, envious, conceited, perverse, and so on.

They have no choice but to be enthusiastic, to think “positively,” to enjoy what they do, and to have fun with the players.

Otherwise – they might as well quit the profession!

To successfully meet all requirements, the instructor must be generous, altruistic, fond of people, willing to sacrifice their habits and often even their parallel personal interests, animated by a sense of duty and respect for their work. They also need to be in very good physical condition. The fact that they are forced to speak a lot, captivatingly, engagingly, with substance, or conversely, to remain silent – when necessary, or to psychologically manage a group with members of very different ages and life experiences, shows how difficult their task is. Therefore, the instructor who loves and respects their “profession” must constantly strive to become a better person, more courageous, more cultured, more competent, with better physical condition, with a broader mental openness. In short, the instructor can teach students what they truly are, not what they think they are.

4.2. Preparation of a Lesson Programme

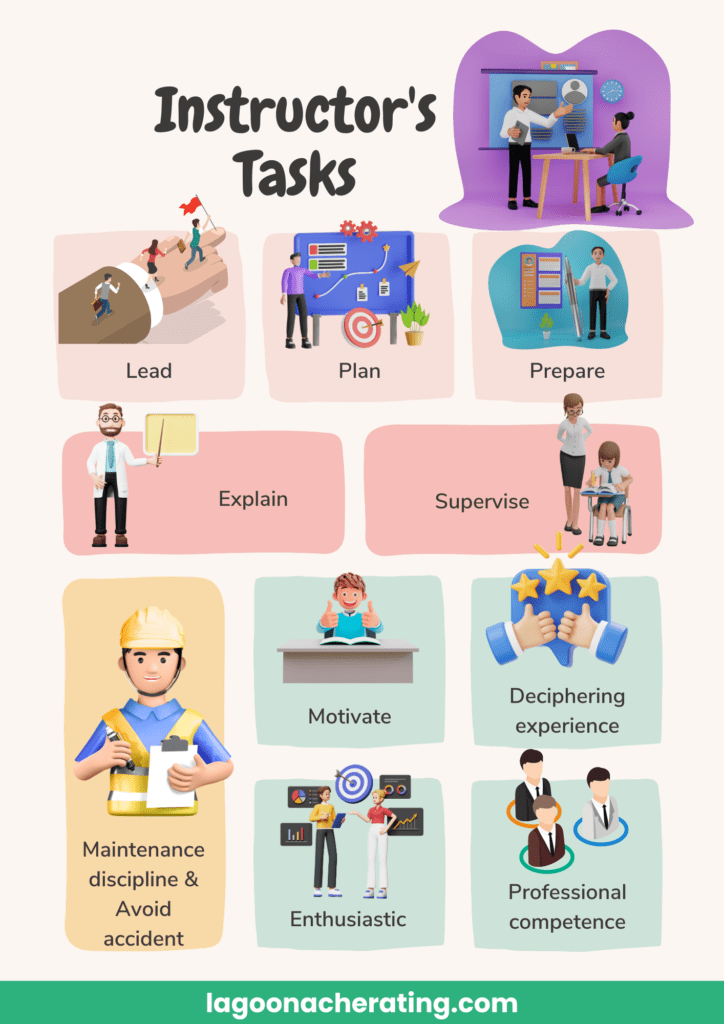

For it to be education – and not just entertainment or even a waste of time (and money!), games must be strictly framed within a well-conceived Team-building lesson/session programme. The responsible action instructor must clarify in advance, together with the Client’s representative (HR manager/school principal, etc.) and their own organization’s leadership:

- The purpose of the action/stage/programme,

- The conditions of conduct (location, time, duration, costs, responsibilities, etc.),

- The material and human resources (instructors) available,

- The characteristics of the participants (students),

- The safe conduct of activities.

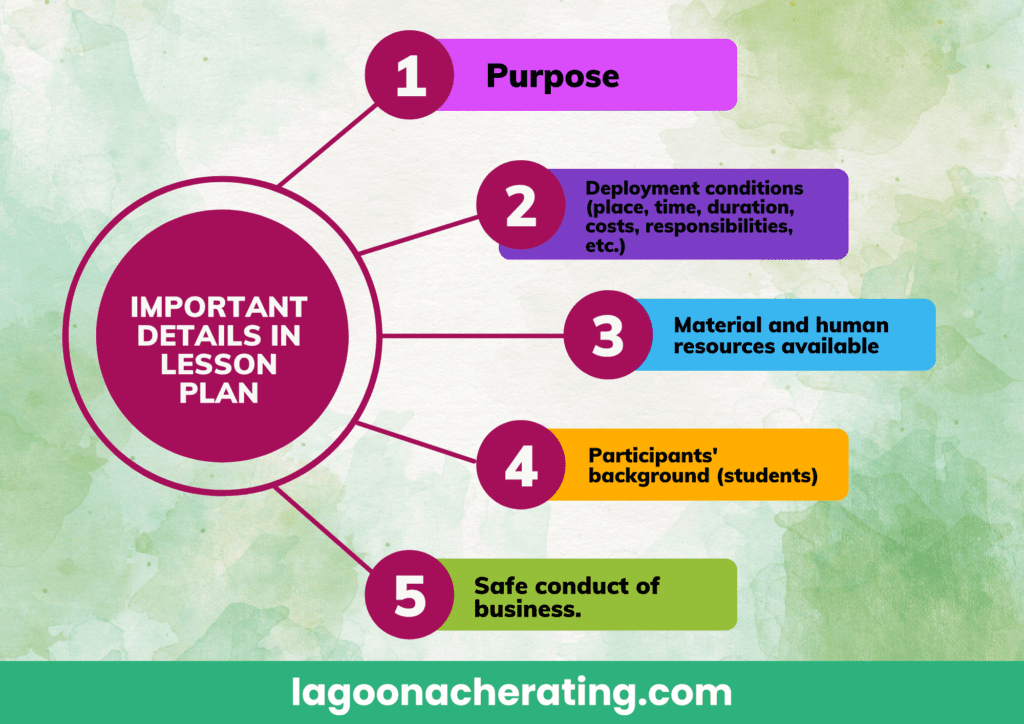

The instructor will consolidate this information and conditions into a written programme, with the following steps:

- Establishing the group’s needs and goals – based on detailed, sincere, responsible discussions with the Client’s representative(s) to align their opinions and requirements with the instructor’s and their organization’s capabilities.

- Planning activities/games appropriate for meeting the needs and achieving the goals – see # 4.4. and # 4.5. The instructor will devise a written programme outline, including: the relevant lessons, their dates and locations, the lesson topics and objectives, the main discussion points for deciphering the experience after each game, etc.

- Presenting the written programme – to the Client’s representative, for a final assessment/confirmation of alignment between their requirements and the planned/proposed activities.

- Conducting the programme/lessons;

- Monitoring the effects of the lessons over time and leveraging the learning transmitted into the students’ professional/social activities.

The programme also has the character of an “educational project,” with all the elements and stages of any project – which the beneficiary (assisted by the instructor) must clearly specify:

- Beneficiary: client, user, funder, etc.;

- Theme (purpose): processing one or more individuals to make them capable of completing established tasks;

- Selection of the executor (fairly: through competition);

- Work plan: documentation, arrangements, actions, responsible parties, costs, deadlines;

- List of necessary and available means and resources (material, human, financial);

- Execution: completing the work, overseeing execution;

- Compliance with relevant legality and standards: occupational health and safety, environmental protection, socio-political-economic-human-international impact;

- Completion: preliminary, testing and verification, remedies;

- Delivery to the beneficiary;

- Guarantee;

- Conclusion;

- Feedback: lessons for the future.

Here are some additional tasks for the instructor:

- They will visit the location(s) of the lessons/programme in advance to understand their configuration and characteristics, so they can potentially include them in the game structure (for example, outdoors: terrain/obstacles/trees/water; or in a sports hall: walls/benches/tables/chairs, etc.). They will also identify and establish the location and access to telephone, toilets, boots, shelters, parking areas, assembly/rest areas.

- They will gather as much information as possible about the participants: how many there are, their physical abilities, their age and background, whether there are participants with special characteristics (disabled, with mental health issues, with special needs, etc.), the ratio of women to men, bosses to subordinates, instructors to students – see also # 4.6.

4.3. Lesson Preparation

If the job you have to do seems simple to you, it means that you have not yet learned everything about it!

Donald Westlake

Training participants, presenting collaborative games, and leading the student group in an effective manner for the success of the activity constitute a challenging task for many instructors (even professionals). Therefore, a few guidelines about the purpose and conduct of the games can be very helpful.

The instructor will prepare the Lesson Plan (mandatory in writing!), well in advance of the session’s scheduled date. The lesson fits into the program’s plan.

Based on the session/lesson plan, a scenario (story) will be devised to guide the conduct of the entire activity, just like in a movie or a theatre play. Then, the instructor will determine the places and surfaces (indoors or outdoors) where each group and subgroup will carry out each activity. They will establish the meeting point, where the presentation activity will take place.

ALL necessary teaching materials are procured, prepared, and checked beforehand, so they are readily available at the start of the lesson. Similarly, inventory is gathered and checked at the end of the lesson – see #16.

Additionally, all participants will be notified in advance about the date and location of the meeting, the duration of the lesson, and the personal equipment required.

Especially if it is an outdoor activity, in adverse weather conditions (rain, mud, wind, strong sun, etc.), the equipment must be appropriate:

- For the session: loose and thick clothing (allowing movement, protecting against cold, dampness, shocks, etc.), comfortable footwear (trainers), gloves, cap, hat, poncho, etc.;

- Towel, warm change of clothes at the end of the session.

The instructor will have a bag with some spare items to meet the needs of forgetful individuals, etc.: drinking water, cap, towel, poncho, etc.

The location where the lesson takes place must have sanitary facilities (drinking water, washbasin, toilet) in good condition.

Each instructor will have a first aid kit (which they must know how to use) and a quick means of communication (mobile phone) with a doctor (Emergency Services). It is strongly recommended that the instructor undergo (and complete) a first aid course.

After each game, understanding (or deciphering) the experience (through discussing the activity conducted) – see #6 – should be as simple and to the point as possible. On this occasion, the instructor will also share from their own personal experience, as their memories as an adult represent a wealth of knowledge for the young listeners.

As the group leader, the instructor must present themselves and behave appropriately. They should be addressed correctly to maintain their prestige and credibility, fostering trust among participants. Sunglasses should only be worn in exceptional circumstances (while eye contact is important, take note that excessive eye contact may be uncomfortable in Malaysian culture). While memorizing the entire participants’ names and using them in conversation is not necessary, it can be beneficial. Enthusiasm is crucial for the success of the lesson as it inspires and motivates participants. The instructor’s mood often sets the tone for the entire group, influencing their engagement.

When the players manage themselves, the instructor must let them take the lead and follow them. If a group shows signs that they want to play all day, let them do it! Let the group show where they want to go, and they will do it!

The instructor will have action plans prepared for undesirable situations: unfavorable weather, or if the group arrives late at the meeting place/time, etc.

The book describes numerous beautiful, appealing, easy-to-play games. Play them carefully to avoid accidents, aiming for the desired goal, have fun, and tire yourselves out!

But when you play, don’t forget that you’re doing serious work!

4.4. Lesson Organization

The issues and objectives to be achieved are established by the group leader and the beneficiary of teambuilding education: teacher, coach, employer or team leader, or social worker, etc. This is a “client” who hires a “provider” (the instructor) to deliver a service (conducting the session or course) of Team Building. Collaboration games are actually the means or tools with which the instructor solves the problems given to him for a particular group.

Usually, a lesson (session) with collaboration games lasts for two hours.

Like any well-done thing, the games session will have a beginning, a content, and an end. All activities carried out in the session can be games, but there are also other good exercises.

The beginning of the session must be attractive and motivating, because it determines the attention and interest with which the students will participate further.

The end of the session must also impress and mobilise the players so that they part with good spirits and pleasant memories, with friendly feelings towards their colleagues and instructor, wishing for a repetition of the experience as soon as possible.

Many teachers and instructors use games at the beginning or end of regular lessons (school, sports, etc.).

Another good idea is to intersperse them within a larger event, between various actions, or as part of another action of the organisation to which the group belongs (school, company).

Games can be a powerful breaker of the monotony of a long school day or exhausting work. They can occupy and soothe young children, but also entertain “adult” children. Sometimes a game can relieve the tension caused by a bad day, other times it invigorates the spirit and cohesion of the team, worn out by the stressful schedule, and sometimes the game stimulates the creativity necessary to solve a difficult problem.

In the course of one session, at most 10-15 games can be played, because the phase of understanding the experience takes a long time. The book presents approximately 180 games, which is enough material for numerous sessions.

4.5. How to Choose the Games?

An important aspect of session planning is the selection of games and their order, the so-called sequence.

When preparing the list of games suitable for the lesson’s purpose, the principle of “succession of games with increasing difficulty” is used.

If the group members do not know each other, or have not collaborated before, at the beginning of the session, a few introductory games are needed (to break the ice), which soften each person’s personal defense shell and reduce the surrounding alarm space that each person has. After the players warm up and lose some inhibitions, avoiding each other less, we can move on to melting the shell and canceling the individual alarm space, proposing basic games. Harder games are played after some easier ones, which have already created a sense of satisfaction for the group’s achievements.

The appropriate sequence means choosing games suitable for solving the group’s real-life problems or goals and arranging them gradually according to the level of difficulty. The program must also include backup solutions.

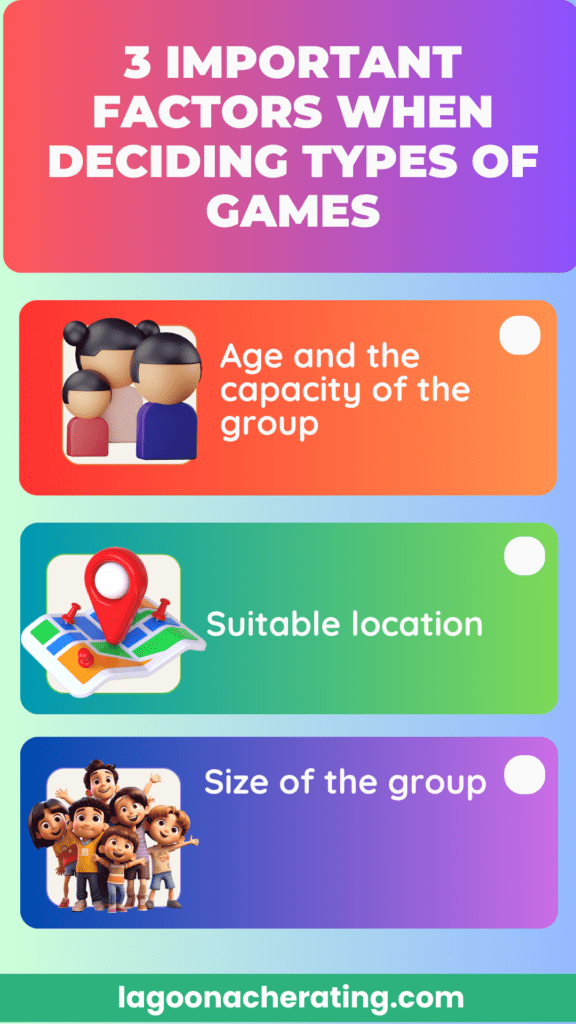

The instructor should consider these three matters to help the group participants get the most out of their experience in the games:

For the group to benefit as much as possible from the experience it will gain, it is good for the instructor to analyze the following aspects:

- The games are chosen according to the age and physical ability of the group. For example, any group quickly becomes frustrated by tasks that far exceed their physical and mental abilities. Sometimes the chosen game is too simple for a group of adults (wrongly chosen game) and the participants do not feel challenged, they quickly get bored, attention and motivation decrease. In this case, either the game rules will be immediately changed (to make it harder) or even switch to another game.

- The game will take place in a suitable location, indoors or outdoors, where accidents are avoided, and participants feel comfortable. Existing materials on the field will also be used: benches, trees, fences, logs, etc.

- The size of the group should be moderate. It is preferable for very large groups (25-30 people) to be divided into two or more equal groups. In excessively large teams, good ideas and intentions are often lost in favor of louder voices or participants with individual popularity (for example, an office manager, etc. from the organization where the players work). Teams, whether it’s one (the entire group) or more (groups), will choose a name through discussions and consensus (funny, but still not “Death to the fat ones”, etc.).

4.6. Group Composition

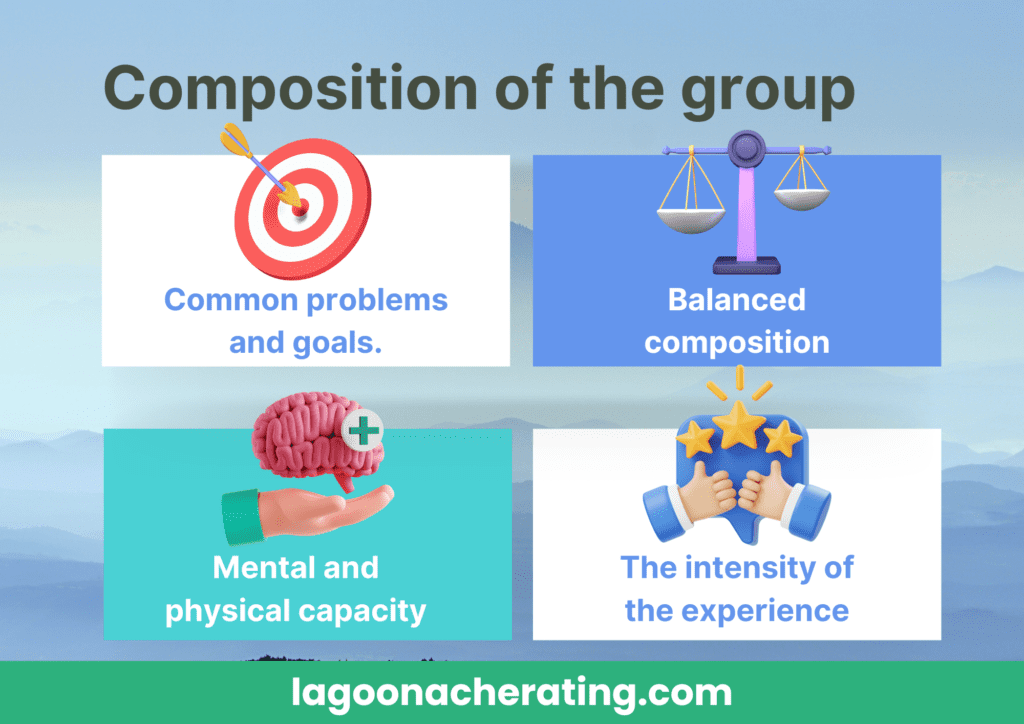

Usually, the group composition is predetermined, mandatory, but there are also situations when criteria can be applied for selecting participants:

- Common Problems and Goals. Due to activities carried out together, group members transition from individuals to teammates, learning to listen, respect, and take care of each other. This group formation process imposes a certain level of uniformity and community of opinions and behaviors on its members. However, some individuals disagree with losing part of their freedom, regardless of the benefits. The instructor will present all these aspects to potential participants from the beginning, and those who do not agree with them will exclude themselves from the activity.

- Balanced Composition. A balanced mix means grouping weaker participants with stronger ones, young with old, leaders with subordinates in ordinary life. This forced interaction yields very interesting educational results. Although the issue becomes important especially if the participants are young people with problems or delinquents, it must be analyzed on every occasion.

- Mental and Physical Capacity. People with disabilities sometimes have greater difficulties in completing tasks required by games. Grouping them with normal players gives them the opportunity to experience feelings they rarely encounter.

- Intensity of Experience. Experiential education is based on the assumption that individuals confronted with significant difficulties rapidly change and develop their personality. Unfortunately, the assumption is not correct in all cases. There are vigorous young people who can make great efforts without suffering (and educating themselves), but also backward patients who need to be handled delicately, as well as indifferent delinquents – for whom appropriate means of motivation must be found.

Categories of players

Participants of any age are divided into several categories:

- Active players, interested in any activity, enthusiastic about engaging others;

- Unstable players, who participate based on the moment’s mood. They form the majority;

- Passive players, in smaller numbers than those in the first two categories, are easily recognized. They require special attention. Shyness or lack of interest have deeper causes. It could be a psychological barrier (embarrassment about their clumsiness, lack of experience, etc.), a real handicap, and so on.

4.7. Conducting the Lesson

Before the lesson, participants should be observed for a moment: what’s the atmosphere like? Are they ready for what’s to come (footwear, clothing, enthusiasm)? If possible, informal discussions should be held with a few participants to find out: what are they expecting? What would they like to happen next?

The instructor’s tasks are:

- to ensure that participants fully understand the purpose of the gathering and the activities that will take place, and to ensure that everyone participates correctly, conscientiously, creatively, and responsibly in them;

- to ensure that participants understand and remember the ways in which the goal is intended to be achieved, such as the rules of the games, tasks and rights of the players, and the role and powers of the instructor (guidance, arbitration, etc.);

- to increase the group’s team spirit by reinforcing the formative effect of the games: good, friendly, and stimulating intercommunication (including jokes, rest breaks, prompt diplomatic interventions to stop potential conflicts).

For optimal time management (time is money!), the instructor will ensure to respect and enforce respect for:

- the established working schedule;

- punctuality;

- discipline and rules of common sense/behaviour.

At the beginning of the lesson, the team-building instructor will discuss with the students the importance of each teamwork principle (see # 2.3.). Relevant examples will be given about how these skills interest students and how they can practically apply them in their professional (or private) lives. Participants will be encouraged to express their opinions.

Before starting a game, its rules will be presented as clearly as possible to all participants. However, both an excess of rules and uncertainties should be avoided.

Presenting the game and its rules in a way that becomes an important and stimulating task for the group is a difficult job for any instructor. To this end, they will also share personal experiences with the group (sometimes embellished and amplified for the success of the action, with: episodes, stories, sensations, invented or copied adventures, in which they were the hero). Regardless of age and biography, any instructor worthy of the title has already accumulated a large amount of knowledge and experience, which they can leverage.

Collaborative games can be presented to participants in many ways. Some instructors invent spectacular scenarios, stories with giants, terrorists, sharks, etc., while others present the game as it is (plainly, directly). Both approaches are correct. Each instructor will choose the teaching method they prefer and feel comfortable with, as their good mood is essential for the success of the lesson.

After presenting the given situation and the game rules, the instructor will step aside and let the group solve the problem as they see fit, even if they sometimes get confused. Since the instructor chose the problem (the game), they probably know the best solution, but it’s of no use if they interrupt the game to give advice or “hint” the “correct” solution. The goal of the entire activity is the interaction between the players, not their physical performance or how quickly they solve the problem.

Sometimes, in the heat of the action, players may break a rule. The severity of the punishment can range from a warning or a time penalty to restarting the game from the beginning. The instructor must strictly enforce the rules of the game. If the group suspects that the rules of the game don’t matter, the activity will quickly degenerate into chaos, with zero functionality and usefulness.

For variety or to increase interest or the level of individual effort, games can be presented in the form of a competition. Such competitions can take two forms: either the group competes with itself, working against the clock and surpassing its own record obtained on another occasion, or the group competes with other (sub)groups or with the (real or ad-hoc invented) time record set by another group or school, etc.

After the group has solved the problem or task (or attempted but failed), the activity experienced (the lived experience) is discussed with all participants (see # 6).

4.8. Informing the Participants

One of the essential conditions for the success of educational action is good communication, in both directions, between the instructor and the students as well as among the students themselves.

Therefore, the participants will be informed about the upcoming activity, their tasks, and the rules to be followed, or about any other aspect they should know:

- At the beginning of the lesson;

- Before each game;

- Throughout the lesson;

- At the end of the session.

The instructor will continuously encourage participants to express themselves and communicate both any misunderstandings or problems they may have, as well as any comments or suggestions regarding the ongoing activity.

Usually, participants do not know what to expect or what is required of them, or they have personal issues that require the instructor’s attention.

Therefore, at the beginning of the session or collaboration, the instructor will inform the participants about the session’s schedule, the general framework in which the activity will take place, and its objectives. At this time, the participants’ issues will also be discussed.

The group works (and self-educates) better if, before starting the “game,” some basic ideas are clarified:

- what we want to achieve through the game (the purpose of the action);

- what the participants have to do; and

- what they will gain from this activity.

For collaborative games to exceed the level of mere entertainment and become learning experiences for participants, they must be presented to students according to certain guiding rules.

The activity can be presented in the form of a scenario or as a story. Thus, for children (but not only), the venue and the game itself can become an ad-hoc fairytale situation, in which the players experience various fabulous “misfortunes” if they do not collaborate with each other.

There are two types of information given to the players: some strict and non-negotiable, related to avoiding accidents, and others negotiable, regarding the rules of the games and the activity’s objectives. In the former case, participants can only request clarification, whereas in the latter category, they can make proposals and comments, and are even encouraged to do so.

The rules of the game and the purpose of the activity must be communicated to the group and clarified together with all participants before each game.

After presenting the basic elements of a game, all players will be invited to a short brainstorming session to specify, add, complete, and fix the game rules and the action’s purpose. It is not good to have too many rules. In the case of adults, the similarity between the game and situations from everyday life will be explained, challenging participants to look for deeper meanings than initially apparent.

There are three main general rules:

- Firstly, to avoid accidents. No compromises that endanger the safety of any participant (including the instructor) are allowed.

- Voluntary participation. It is important to convey the idea of the “voluntary acceptance of participation” to the students. It should be clear to each player that their physical participation in any game is voluntary. If someone does not want to participate in a game after learning the rules and the game’s purpose, that’s fine! However, all group members must participate in all group activities, so those who are afraid to play will receive “important” tasks such as: rescuer, observer, referee, statistician, etc.

- Everyone should feel good, even have fun.

It is recommended to create written sheets on A4 paper with various important information: the basic rules (#7.3), words of encouragement for colleagues (#8.1), the list of exercises and games to be practiced during the session, etc. These sheets will be duplicated (possibly laminated) and distributed to the students – to be collected at the end of the session for reuse on another occasion.

4.9. Leading a Group

The science of effective leadership shows us that the leader of a team has three general duties:

- Creating conditions that allow the team’s tasks to be fulfilled,

- Forming and maintaining team unity,

- Training and supporting team members.

And three functions:

- Leadership,

- Management, and

- Training team members.

Leadership (strategic) means guiding the team in the long term, through appropriate interventions to motivate collaborators.

Management means medium-term planning and clarifying the team’s objectives, as well as providing feedback on individual performances.

Training (operational leadership) means allocating tasks through daily direct contact with collaborators, as well as addressing current issues arising from concrete activities for operational resolution.

The science of effective leadership can be learned.

Learning from experience is the most common and reliable. It produces tacit, emotional knowledge crucial in moments of crisis, but experience and intuition can be reinforced by analytical knowledge.

The ability to analyze situations and contexts is an important talent when you want to lead. However, the most important thing remains experience and the ability to learn from mistakes – a continuous process resulting from what the military call “post-action observations” or feedback.

The learning process can sum into three words: “Be, Know, Do.”

“Be” refers to shaping character and values. This is partly achieved through exercises and partly gained from experience.

“Know” refers to skills and situational analysis – which can be educated.

“Do” refers to action and involves both exercise and field practice.

In the case of team-building activities, the instructor leads the group throughout the session without deviation in one direction (i.e., weakening supervision, rigor, etc.) or another (i.e., reducing concern or responsibility for accidents).

However, practical, apparent leadership of the group can be delegated through rotation to group members – see #4.14. This can accelerate the development of leadership skills in some of the more promising participants and create a sense of responsibility in those who are shy, isolated, etc.

Any successful leader or entrepreneur soon realizes that to continue thriving, the organization or enterprise they have founded has only two options: either to stagnate and die, or to grow. If it grows, it means hiring new employees, more and more. This increase in personnel poses a vital problem for the entrepreneur: how to lead them?

Leadership can be done in two ways: either following the authoritarian, autocratic model, or following the cooperative model – the team’s model.

Although everyone imagines they could be a born leader, the role of an effective leader is difficult to fulfill well, with happy results. There is a huge difference between the profiteer who leads only to dominate subordinates (i.e., solely for his own benefit) and the leader who leads to enhance the group’s (economic, emotional, human) performances (for the collective good). The traditional boss tends to give orders instead of seeking advice and mediating. He tries to impose opinions authoritatively instead of coordinating team members, supporting and encouraging them to excel.

A true leader inspires people to dream, to learn, to do more, to grow more, to create a better future for themselves.

Group/team activity is based on the voluntary, competent, and responsible participation of two partners: leader and subordinates. Unfortunately, the competence and responsibility of one partner can only compensate to a small extent for the incompetence or irresponsibility of the other partner. Thus, the “good” boss soon finds out that there are subordinates who “sabotage” the common activity through their behavior, just as the “good” subordinates find out (too soon) that the boss is corrupt, dictatorial, etc.

In our education system, there are no lessons on leadership, so often adults who become bosses due to professional merits (“know their job”) or due to “connections” (have influence, etc.) quickly realize their managerial incompetence. To avoid losing their position (and respective advantages), they become “tough,” “masters,” corrupt, and corrupting, to impose their authority at any cost. There is no mention of specific leadership knowledge or skills, teamwork, increasing efficiency, or competitiveness.

Poor productivity and the feeling of “spinning one’s wheels” at work are well known here. They are largely due to incompetent (but pretentious) bosses.

The problem of incompetence in leadership could be solved with the help of Team Building.

Let’s analyze some aspects of leadership applicable to the team-building instructor’s situation and collaborative games:

4.10. Common Interests

The instructor largely identifies with the group, being an active member who leads but also participates alongside other players, experiencing (more or less) the same feelings. Usually, the participants manage on their own, they don’t need sophisticated instructions or military commands, but both they and the instructor are aware of the necessity and importance of the competence, supervision, and control of an expert (adult).

The instructor is both an external factor to the group and an internal one.

There are also activities in which the instructor cannot participate as a player because they are compelled to oversee the safety of the proceedings.

4.11. Motivating Through Challenges

The instructor will encourage and challenge the players to participate wholeheartedly in the proposed games.

A response to a suitable, challenging challenge will lead the individual to overcome routine, efforts, and usual results, to reach new areas, forcing them to do what they haven’t done before, to confront the fear of the unknown and the feeling of helplessness, to accept the help and support offered by teammates. The challenge also means looking into the depths of one’s soul, where fear and uncertainty about doing, deciding, and being emerge. The challenge can back someone into a corner.

But the challenge is a double-edged sword. It offers both the opportunity for satisfying change or success, and the overwhelming possibility of failure, injury, or falling into ridicule. Where there are conditions for development, there inevitably arises the possibility of overreaching, of exerting too much effort, of stretching beyond what is feasible – which delays the growth and development of participants, thus condemning them to failure and nullifying one of the main purposes of the entire educational action.

4.12. Voluntary Participation in Games

For years, it has been believed that the success of experiential education (i.e., learning by doing; or workplace learning) requires a military-like attitude from the instructor, who had to push all students to the limit of their personal capabilities, into the realm of physical and mental suffering, without regard for their feelings.

For instance, the “training” or “taming” of army recruits through mistreatment by the “elders,” during the advanced stages of their training, is well known. Or the “rite of passage” from youth to adulthood, practiced by certain tribes, a test to prove the young person’s maturity and ability to care for themselves under harsh conditions. The test consisted either of hunting a large and dangerous animal alone (a bear, among Native American tribes), or stealing a valuable object from the neighboring village (among Africans), etc. The young candidate prepared seriously for the “exam”, as they knew the consequences of failure: the bear they hunted could disfigure or kill them; if caught by the aggrieved villagers, they would face a beating akin to death, and so on.

Although they may seem barbaric, these methods of physical and mental preparation, confirmed by centuries of experience, satisfied the survival needs in the respective harsh living conditions.

Today, education is mass-oriented, and the consequence of failing a “baccalaureate” cannot be disfigurement or death anymore.

Studies have shown, however, that effective schooling can be done without horrendous torments, that the freedom given to students to choose between doing – and not doing – a certain task produces educational results just as good for the mind (although it does not improve their personal physical performance). This new conception frees both the instructor and the students from constraints and sometimes difficult-to-accept and bear mental burdens, allowing for the maximisation of the number of participants from the overall population.

The voluntary participation of an individual in group activities that seem to push their own limits offers them:

- The opportunity to try performing an action that appears dangerous (to them), within an atmosphere of understanding and mutual aid;

- The freedom to back off or give up when the stress of achieving “performance” becomes too strong, knowing, however, that they can try again at any time;

- The chance to safely attempt difficult tasks, knowing that the attempt is more important than the result;

- Respect from others for their opinions and decisions.

Voluntary participation does not mean skipping, or laziness, or slyness. Students came to class to get a job done; they have a common goal (agreed upon from the outset) and it must be achieved. Voluntary participation means, for the participant, to think maturely about how they can solve the task or how they can substantially contribute to its completion together with their teammates, then to sincerely and with “all” their might try to get the job done, and if they feel they can’t do it because they might get injured, only then to temporarily give it up. The instructor should be firm in this regard!

Here are a few ideas (see also #4.7):

- It’s important to specify, from the outset, the goal of the game (regardless of the game, the goal is the same: team spirit formation, learning to participate in common activities) and have it well understood by the players. “Beginning” means either the briefing session at the beginning of the lesson, or the short presentation discussion of the respective game, or even a possible personal discussion, during the activity, between the instructor and the person with issues. When the purpose of the activity is well understood, students feel better and act more efficiently.

- It’s not obligatory for each participant to become a champion, or to do everything that others do. But it’s important to contribute in some way to the team’s success. It’s the instructor’s task to find appropriate tasks (auxiliary, simpler, etc.) even for the players with issues.

- Choosing a well-graded succession of games can contribute to increasing the participants’ confidence in their own abilities and overcoming their mental barriers. Maintaining a high level of collective enthusiasm throughout the lesson is an important task for the instructor.

- The psychological pressure of the group on its members is a powerful influencing factor that must be skilfully utilised, constructively. Therefore, difficult games should be left for later, after the students have become familiar with the group and have confidence in each other. The psychological pressure should appear as support given by the group, not as persecution. But beware: colleagues’ concern for a teammate can easily turn into abuse or harassment. So – with measure!

- Without mutual trust, the tasks (homework) of some more difficult games will not be accomplished. The low level of trust shows that the participants have not yet played enough trust games, or they have not been well led by the instructor to be effective (they have not been repeated enough, etc.).

- The instructor must inject fun and fantasy into the group’s activity continually.

4.13. Collaboration Agreement

The objectives of the activities within the session will be jointly agreed upon by the instructor and students in the form of a Collaboration Agreement, based on two main ideas: teamwork and accident avoidance.

The agreement consists of three basic commitments:

- Each participant’s agreement to work together with others in the group to achieve the agreed-upon goals;

- Each individual’s agreement to adhere to certain safety and behavioural rules;

- Each participant’s agreement to give and receive both positive and negative feedback, as well as to strive to change their behaviour if necessary.

The agreement is discussed and harmonised with the participants as early as possible during the session. Adhering to it means for a participant not only accepting the group’s behaviour but also avoiding disrespect towards other players or even oneself. However, group interactions must be carefully managed by the instructor. Even if the other twenty teammates speak the truth, sometimes the blunt revelation of their opinion about a colleague can be a devastating psychological shock for that individual.

4.14. When does the instructor intervene?

During the session, throughout each game, the instructor will fully engage in the activity but will also have fun. They can be as meticulous or as relaxed as they wish. After the game ends, they will bring the players’ thoughts back to reality by discussing the activity carried out (deciphering the experience – #6).

However, the instructor will intervene as little as possible as a leader in the group’s activities. The game acts with great educational force on the participants precisely through the lack of external instructions and constraints, by the task of thinking and judging with their own minds.

But there are also cases when their intervention is necessary, even interrupting the activity, such as: to calm down the pace of the game when it risks becoming dangerous, or to end a conflict, or to modify rules that prove inadequate, etc. Students benefit greatly from hearing the constructive and transparent discussions between the instructor and some players for resolving a conflict that could otherwise escalate into a critical situation, in which case drastic measures would be necessary. Most people do not encounter such things in their lives. Usually, conflicts are postponed, “forgotten,” hidden, left to smolder (until they explode!).

Here are a few examples of intervention:

- The game is interrupted, and the participants are gathered for a (so-called) short technical training session – whether the information was really necessary or the stop was made to discreetly restore discipline. Instructions like how to approach a partner, or how to hold onto them, how to blindfold yourself, etc., can be given. This type of intervention is not perceived with hostility by the participants, as everyone knows they have something to learn from the instructor. Since the session refocuses everyone’s attention on the instructor, they can easily manipulate the group in the desired direction, namely to avoid accidents, extinguish conflicts (even those not yet triggered), and reinforce a positive atmosphere.

- Changing one game to another more suitable: if the game does not match the group’s specific characteristics (for example, the instructor chose a game too simple for participants who prove to be smarter than anticipated).

- Changing the rules of the game, either by the instructor’s unilateral “decree” or by democratic consultation with all players. Changes can range from blindfolding to “freezing” players in place and memorizing everyone’s positions (see #6.4.1. – 6), to:

- Interrupting the game and moving directly to “analyzing/ deciphering the experience” when the group takes too long to solve the task, it gets late, or some participants get bored and start skipping, etc.

- Discussing how the Collaboration Agreement. is being respected. This pedagogical trick allows for the reconsideration of any aspect of the game or activity to improve the situation. The question “do we respect the commitments agreed at the beginning of the session?” can be repeated whenever necessary. This way, indiscipline, activities unrelated to the game, bad jokes, challenges, insults, pushes, etc., are curtailed. In general, participants are pleased when the Agreement and the obligations arising from it are reminded, as in the heat of action, some players forget about them and (involuntarily) create tense relationships with others.

4.15. Delegating Leadership Tasks

If necessary, when there are multiple teams (groups), for the smooth running of the session, each team will choose a member to perform one of the following tasks: an organizer, an animator, a reporter. If the group constitutes a single team, all these tasks can be performed by the instructor.

The organizer (leader) directs the team’s activity (under the guidance and supervision of the instructor). He receives a sheet (possibly laminated in plastic) containing the name of the game, the necessary equipment, the rules and the task of the game, penalties, and the control questions addressed to the team. These questions aim to ensure that all participants understand what they have to do. Until team members satisfactorily answer the questions, the organizer does not signal the start of the game.

Examples of questions:

- What auxiliary materials will we use?

- Where do we start?

- What are the rules?

- What are the penalties?

- Where do we need to get to?

- What happens if we touch the rope?

- How long do we need to stay there?

- How do we know we’ve completed the task?

- Where will the materials be at the end of the game?

- How can we help each other?

- What will be heard during the game?

- What happens if one of us behaves badly towards a teammate?

If the team fails to solve the game task after several attempts, the organizer can ask for advice from the instructor; but be careful: too much help cancels out the educational effect of the activity! Students must try hard on their own until external help becomes appropriate.

The animator’s task is to praise various collective actions of the team, both during the game and after its completion (unlike other teammates, who only praise their neighbor or partner).

The reporter will report to the instructor (who could not continuously monitor the activity of each team because he was supervising the others) how his team solved the game’s theme, what was fun, and what was difficult, what the team thinks should be changed in the game rules, etc. The reporter then presents the same information in front of the assembly of all teams (if applicable).

The report will consist of answers to the following questions:

- How did each member of our team get involved in solving the game task?

- During the game, were there any expressions of deprecation towards teammates? (see # 6.4.2.)

- Did we listen to each other and use the solution ideas proposed by teammates?

- How many and which teammates used words of appreciation? (see # 8.1.)

- What were the expressions of appreciation heard during the game?

4.16. Together – or “Me First”?

Collaborative games are the opposite of competition, but unfortunately, despite everyone’s goodwill, participants cannot completely escape the effects of a lifetime of education during the session. The skill of the instructor lies in using the competitive spirit – which will inevitably arise – to achieve the goal of the lesson, namely: building teamwork spirit, increasing group unity, and strengthening students’ personalities. In this sense, participants will be directed to excel not with their teammates but with themselves, or with an obstacle, or with a record (perhaps imaginary), but always with pleasure, without stubbornness.

Here are some suggestions for non-competitive criteria for measuring the team’s success that the instructor can use:

- Timing the duration of the activity;

- How many players manage to overcome, or go through, the obstacle within the available time;

- How well the rules are followed (for example: not touching the rope, not letting go of hands, etc.);

- Show the spectators (parents, etc.) how well you perform (without giving rise to an “us against them” attitude);

- Emphasize the reasons that prevent us from succeeding; those are the enemies – not other people, etc.;

- The instructor will ensure the group’s certain success by using games with difficulty suitable for the participants’ abilities. Nothing helps more than the disappearance of negative thoughts and the fear of failure;

- The instructor will insist on compliance with the Collaboration Agreement. The concern of some players to make a good impression on their teammates or the instructor can lead to conflicts among group members;

- The instructor will adjust the game rules to eliminate the possibility of competition. Participants will be involved in this work (as a form of developing their initiative), and they will be very pleased;

- If the group feels like playing a competitive game at some point, they will be allowed to do so. The score doesn’t matter; it’s the opportunity to run, score, catch, etc.

4.17. Motivating with Humour

Although fundamentally serious, team-building games also aim for the players’ enjoyment, “learning with joy.” In other words, positive social, educational, or corporate changes can be supported by fun!

It can be said that “fun educates.” Students should enjoy playing, leave the session with a smile on their faces, and look forward to its repetition for more fun. If the instructor doesn’t inject a bit of humor into the activity from time to time, the students will mentally tire, become bored, and react half-heartedly, reducing the educational effect.

Here are some suggestions in this regard for instructors:

- Don’t take what you’re doing too seriously – nor yourself.

- The rules of the game can be changed; they’re not set in stone. What matters is not the rulebook rule but the one that makes the group participate with pleasure.

- Don’t skimp on the number of crocodiles in the river to be crossed, storms on the horizon, tornadoes around the corner, cannibals hidden behind the gymnastic box, and so on – meaning the dangers threatening players who delay solving the game’s task.

- Don’t use ordinary objects as teaching materials for games. When they see a football, students “know” what’s coming, and their attention drops. Some who are adept at football start to organize themselves as stars, while others who are less skilled begin to regret coming, and the majority continue to participate without enthusiasm.

Instead, use balloons, plastic bottles, dolls, balls made from old socks, etc., unusual and comical objects. - Give games and objects original, strange, and comical names.

4.18. Keeping Composure

No matter how good a plan or work schedule is, it cannot foresee every possibility. That’s why the instructor must be mentally prepared to deal with undesirable or unforeseen situations – unfortunately, they are inevitable.

Such situations may include: unfavorable weather conditions; the impossibility of arrival for one or more participants (due to car/train/elevator breakdowns, etc.); a power outage; the unavailability of the planned location for the activity; the illness or injury of one or more players; the spontaneous coalition/revolt of some participants against a colleague or the instructor, and so on. Especially in such cases, the instructor must not allow themselves to be overwhelmed by panic, emotions, haste, despair, hysteria, fatigue, etc.

Thorough preparation and consideration of possible solutions can be very helpful. For example, acquiring as many phone numbers as possible from those who contribute directly or indirectly to the stage’s realization or can help remedy the situation: transport companies, repair workshops, etc.

Another solution is to provide a list of priorities and alternative solutions, such as: if an accident occurs – who will attend to the injured and who will continue to lead the group/activities; if the planned location is unavailable – where the activity will be moved; if the restroom doesn’t work – how requests will be addressed, and so on.

But – nothing can replace experience!

So, practice and apply what you learn from the book whenever you find an opportunity, in any gathering/group, even if it’s not a formal team-building session. Organize it yourself ad-hoc. For example, at a family reunion, a meeting with friends or colleagues, etc. Gather experience to become a good team facilitator, to increase social cohesion (and happiness!) in the groups you are part of!

4.19. Cultural Sensitivity: Ensuring Respectful Interaction Among Participants AND Instructors

Being mindful of cultural norms regarding physical contact, especially within Muslim participants, requires utmost sensitivity. With strict guidelines prohibiting physical contact between unmarried men and women, it’s crucial for team building instructors to approach this aspect with great care. Here’s how to navigate it effectively:

- Understanding Cultural Boundaries: This entails maintaining a respectful distance when interacting with members of the opposite gender.

- Respecting Religious Guidelines: For Muslim participants, it’s crucial to recognize and honor the religious guidelines that prohibit physical contact between unmarried men and women. Any form of touching in this context is strictly forbidden and must be avoided at all costs.

- Prioritizing Modesty and Respect: Encourage participants to adhere to modest dress codes, for Muslim participant as outlined by Islamic teachings.

By navigating cultural norms surrounding physical contact with sensitivity and respect, instructors can create a safe and inclusive space for team-building activities.

Additionally, when involving Muslim participants, it’s highly encouraged to implement gender segregation among unmarried individuals whenever possible to uphold strict adherence to Islamic principles regarding physical contact between unmarried men and women.

CONTINUE READING:

Malaysian Guide to Team Building

- CHAPTER 1 : Non-Formal Civic And Entrepreneurial Education

- CHAPTER 2 : The Team Spirit

- CHAPTER 3 : Team Building Education

- CHAPTER 4 : Guidelines for Team Building Instructor

- CHAPTER 5 : Safety & Accident Avoidance

- CHAPTER 6 : Understanding The Experience

- CHAPTER 7 : Introductory Games

- CHAPTER 8 : Warm-up Exercise & Games

- CHAPTER 9 : Calming Games

- CHAPTER 10 : Relaxation Games

- CHAPTER 11 : Creativity Games

- CHAPTER 12 : Cooperation Games

- CHAPTER 13 : Communication Games

- CHAPTER 14 : Trust Games

- CHAPTER 15 : Fun Games

- CHAPTER 16 : Closing Games

- Conclusion

- ANNEX

- Proofreading & Editing